WHY YOU SHOULD ALWAYS PROVIDE PRICING OPTIONS

By Tim Williams

Imagine a coffee shop in which there is only one size coffee. Or an electronics store that sells only one size TV. In the consumer goods world, we are surrounded by options. Small, medium, large, extra-large. Would it make sense for a professional firm — like an agency — to do the same?

From the perspective of pricing psychology, there’s a powerful reason why we as buyers are almost always presented with options: there is no such thing as absolute value. To evaluate a price, buyers require context. Unless we can compare our purchase choice to something else, it’s infernally difficult to ascertain whether the price asked is worth the value provided.

Freedom of Choice

As WPP’s Rick Brook observes, "Not offering options is like holding a Soviet election.” Or a Soviet-era fashion show, as parodied in the seriously comical Wendy’s commercial from the 1980s.

When professional firms offer up a single price (usually in the form of an “estimate”) to their clients, they fail to provide the context clients need to ascertain value. Which is why the majority of other businesses — from car washes to software companies — are now firmly in the habit of providing pricing options for their products and services.

When you equip clients and prospects with options, you’re not only providing immensely useful decision-making context, you’re also fundamentally altering the dynamics of the agency compensation game. Offering different options changes the dialogue away from “How many hours will this take?" to “Which of these options would work best?” Showing different combinations of program elements and deliverables keeps the conversation focused on what clients really buy: outputs, not inputs.

Elements to Consider In Options

Depth of discovery work

Number and nature of program elements

Degree of customization, number of versions, number of revisions

Timing

Pre-testing

Degree of client help or involvement, hand-offs to internal teams

Intellectual property ownership

Measurement and analytics

Socializing the program within the client organization

Applications to other marketing channels

Data archiving

Any other elements that are important to your client

Choice Architecture in Pricing

Offering pricing options is essentially practicing “Choice Architecture,” one of the key tenets of behavioral economics described in the book Nudge. Rory Sutherland of OgilvyChange observes that we navigate the architecture of choice much as we navigate a shopping mall. Professional sellers can design choices in the same way road planners design different ways to get to your destination.

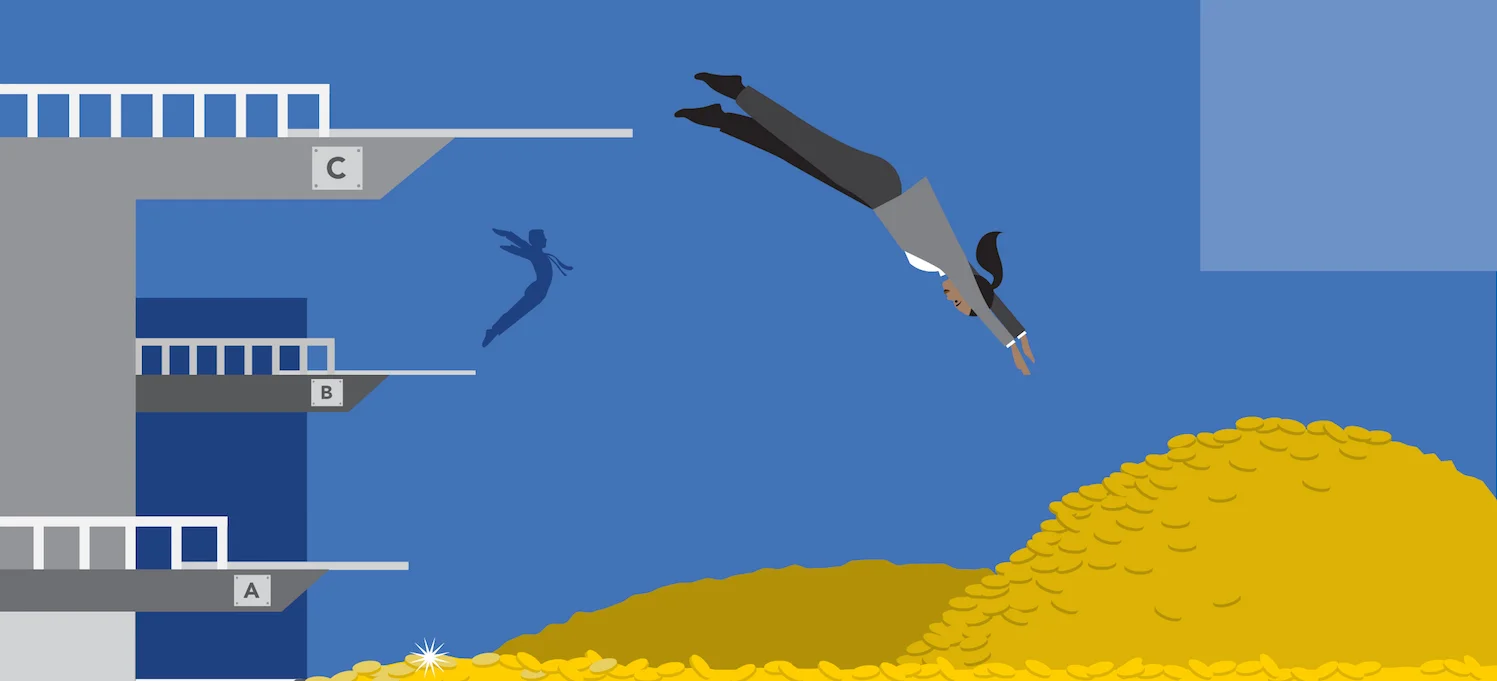

When you present a single price, you’re serving up a take-it-or-leave-it choice. Options change the question from if you want to work together to how you want to work together. As pricing professional Dr. Alan Weiss preaches, never frame your pricing as a “yes” or “no” choice; instead, present your clients with a choice of “yes’s.” McKinsey has compiled statistics over the years that show how providing “different flavors of the same thing” can improve your firm’s chances of selling in a solution by at least 30%.

Key Guidelines in Developing Options

A study of 386 pricing pages for SaaS companies yields some enlightening insights. The average number of options is 3.5. Almost half highlight a particular option (usually the middle). 85% of the options are named. Close to half have a benefit-oriented title. For professional firms, here are some key guidelines to follow:

Provide at least three options.

Give each option a benefit-oriented title

Make the first option your highest price (this is the concept of an "anchor" price). As the buyer reads from left to right, the pricing goes down, not up.

For each option, first describe the desired outcomes, then list the recommended or required outputs. (You may sometimes want to describe the supporting inputs — such as team structure — but never hours.)

Given that the middle option is most often selected, make sure it includes the elements required to produce the desired outcome for your client.

IPA Finance Director Tom Lewis offers the sobering observation that “Our industry has collectively turned left in the supermarket of pricing options, going straight to the aisle marked "inputs-based"; we have struck the category of pricing from our shopping list and opted for "billing" as the sole option.” Actually, when we follow our historical instinct to present just a single price, we’re still subject to the dynamics of choice architecture. Behavioral economist Nick Southgate points out there’s no such thing as neutral design in choice architecture. A single price is the equivalent of a default choice, and as we know from other markets, many buyers would prefer something other than the default.